Bank cards with a chip are designed so that it doesn't make sense to clone them with skimmers or malware when you pay using the card's chip rather than a magnetic stripe. However, several recent attacks on American stores show that thieves are exploiting weaknesses in the implementation of this technology by some of the financial organizations. This allows them to bypass the chip cards and, in fact, create usable fakes.

Traditionally, plastic cards encode the owner's account data in plain text on a magnetic stripe. Skimmers or malware secretly installed in payment terminals can read data from it and write it down. This data can then be encoded onto any other magnetic stripe card and used for fraudulent financial transactions.

More modern cards use EMV technology (Europay + MasterCard + Visa), which encrypts the account data stored on the chip. Thanks to this technology, each time the card interacts with a terminal that supports chips, a one-time unique key is generated, which is called a token or cryptogram.

Almost all cards with a chip store the same data that is encoded on the card's magnetic stripe. This is done for backward compatibility, since so many sellers in the US have not yet switched to chip-enabled terminals. This dual functionality also allows cardholders to use a magnetic stripe if the card chip or merchant's terminal is not working properly.

However, there are several differences between data stored on an EMV chip and data on a magnetic stripe. One of them is a chip component called "integrated circuit card verification code", or iCVV, which is also sometimes called "dynamic CVV".

iCVV differs from the CVV card verification code stored on magnetic tape and protects against copying data from the chip and using it to create fake magnetic stripe cards. Both iCVV and CVV are not associated with the three-digit digital code printed on the back of the card, which is usually used for payment in online stores or card confirmation by phone.

The advantage of the EMV approach is that even if a skimmer or virus intercepts information about a card transaction, this data will only be valid for this transaction, and in the future it should no longer allow thieves to make fraudulent payments.

However, for this entire security system to work, the backend systems deployed by financial institutions that issue cards must verify that when the card is inserted into the terminal, only iCVV is issued along with the data, and vice versa, that when paying with a magnetic stripe, only CVV is issued. If this data does not match the selected transaction type, the financial institution must reject this transaction.

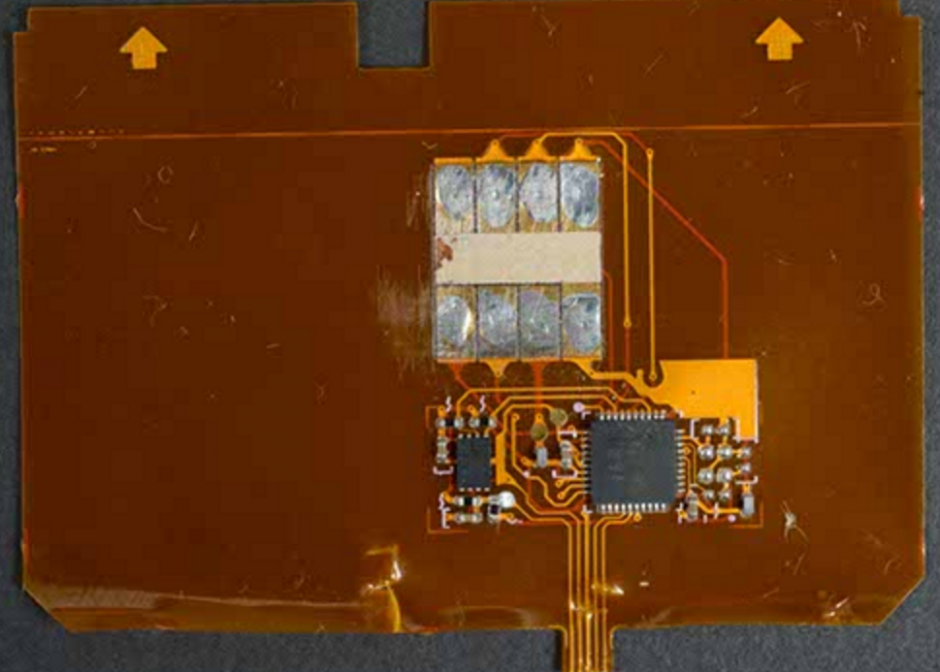

The problem is that not all organizations have set up their systems correctly. No wonder thieves have known about these weaknesses for years. In 2017, I wrote about an increase in the percentage of use of "shimmers" – high-tech skimmers that intercept data from transactions made using a chip.

Shimmer detected in a Canadian ATM

Recently, researchers from Cyber R&D Labs published the results of a study in which they tested 11 types of chip implementation on cards from 10 different banks in Europe and the United States. They found that they could take data from four of them, then create cloned cards with a magnetic stripe, and successfully use them for payments.

There is every reason to believe that the method described in detail by Cyber R&D Labs is used by malicious programs installed in store terminals. The programs intercept transaction data from EMV, which can then be resold and used to make copies of cards with a chip, but using a magnetic stripe.

In July 2020, Visa, the world's largest payment network, issued a security alert regarding the terminals of a recently compromised merchant. In their terminals, malware has been fixed to work with cards with a chip.

"The implementation of secure payment technologies such as EMV Chip significantly reduced the benefits of account payment data for third parties, since this data includes only the personal PAN account number, iCVV card verification code and data expiration date," Visa wrote. – Therefore, with proper iCVV confirmation, the risk of forgery was minimal. In addition, many merchants used P2PE data encryption terminals that encrypt PAN, which further reduces the risk of making payments."

The name of the seller was not mentioned, but something similar, apparently, happened in the supermarket chain Key Food Stores Co-Operative Inc., located in the north-eastern United States. Initially, Key Food revealed details about the card hacking in March 2020, but in July 2020 updated the statement, clarifying that data on EMV transactions was also intercepted.

"The terminals in the stores supported EMV," explains Key Food. "In our opinion, malware during transactions at these points could only intercept the card number and expiration date (not the owner's name or internal confirmation code)."

Technically, the Key Food statement can be considered correct, but it embellishes the reality – the stolen EMV data can still be used to create variants of magnetic stripe cards, which can then be used at those cash registers where malware terminals are installed, when the bank that issued the card did not implement EMV protection correctly.

In July, Gemini Advisory, a company that specializes in fraud protection, published a blog entry detailing the recent hacking of sellers – including Key Food-as a result of which data on EMV transactions was stolen, which then appeared on sale in illegal stores for carders.

"Payment cards stolen during this incident were offered for sale on the dark Web," Gemini explains. " Shortly after the discovery of this incident, several financial institutions confirmed that all the cards involved were processed through EMV, without relying on magnetic stripe as a backup method."

Gemini says it has confirmed that another security incident at a Georgia liquor store also compromised EMV transaction data, resulting in it later appearing in the dark web on sites selling stolen cards. As Gemini and Visa noted, in both cases, proper confirmation of iCVV data from banks should have made this data useless for fraudsters.

Gemini determined that the sheer number of affected stores indicates that it is very unlikely that thieves intercept EMV data using manually installed EMV shimmers.

"Given the impracticality of such tactics, we can conclude that they used a different technique to infiltrate payment terminals and collect enough EMV data to perform EMV Bypass Cloning," the company wrote.

Stas Alferov, Gemini's director of research and development, said that financial institutions that do not conduct such checks lose the ability to track cases of misuse of such cards.

The fact is that many banks that have issued cards with chips believe that as long as they are used for transactions using a chip, the risk of cloning them and selling them on underground markets is practically nonexistent. Therefore, when these organizations look for patterns in fraudulent transactions to determine which sellers equipment was compromised by malware, they can completely lose sight of payments made using chips, and focus only on those cash registers where customers swiped the card with a stripe.

"Card networks are beginning to understand that there are now many more hacks of EMV transactions," Alferov said. – Larger card issuing organizations, such as Chase or Bank of America, already check for iCVV and CVV inconsistencies, and reject suspicious transactions. However, smaller organizations clearly don't do this."

For better or worse, we don't know which financial institutions implemented the EMV standard incorrectly. Therefore, you should always carefully monitor your card expenses and immediately report any unauthorized transactions. If your bank allows you to receive text messages about transactions, this will help you track such activity almost in real time.

(c) Original author: Brian Krebs